The Copenhagen Firewall

How Denmark’s Left Hacked Populism

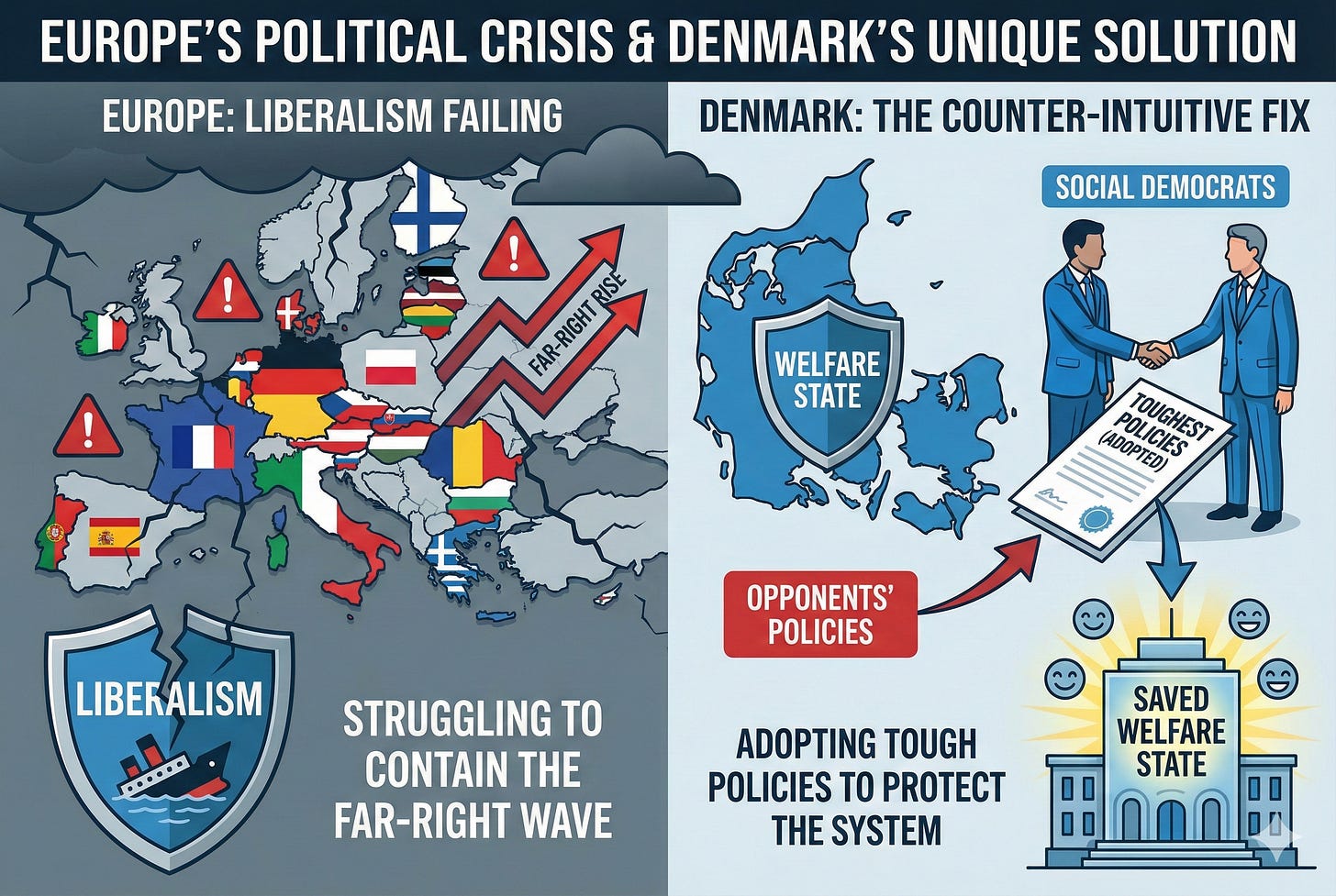

Across Europe, liberalism is failing to contain the far-right. In Denmark, social democrats found a counter-intuitive fix: adopt their opponents’ toughest policies to save the welfare state.

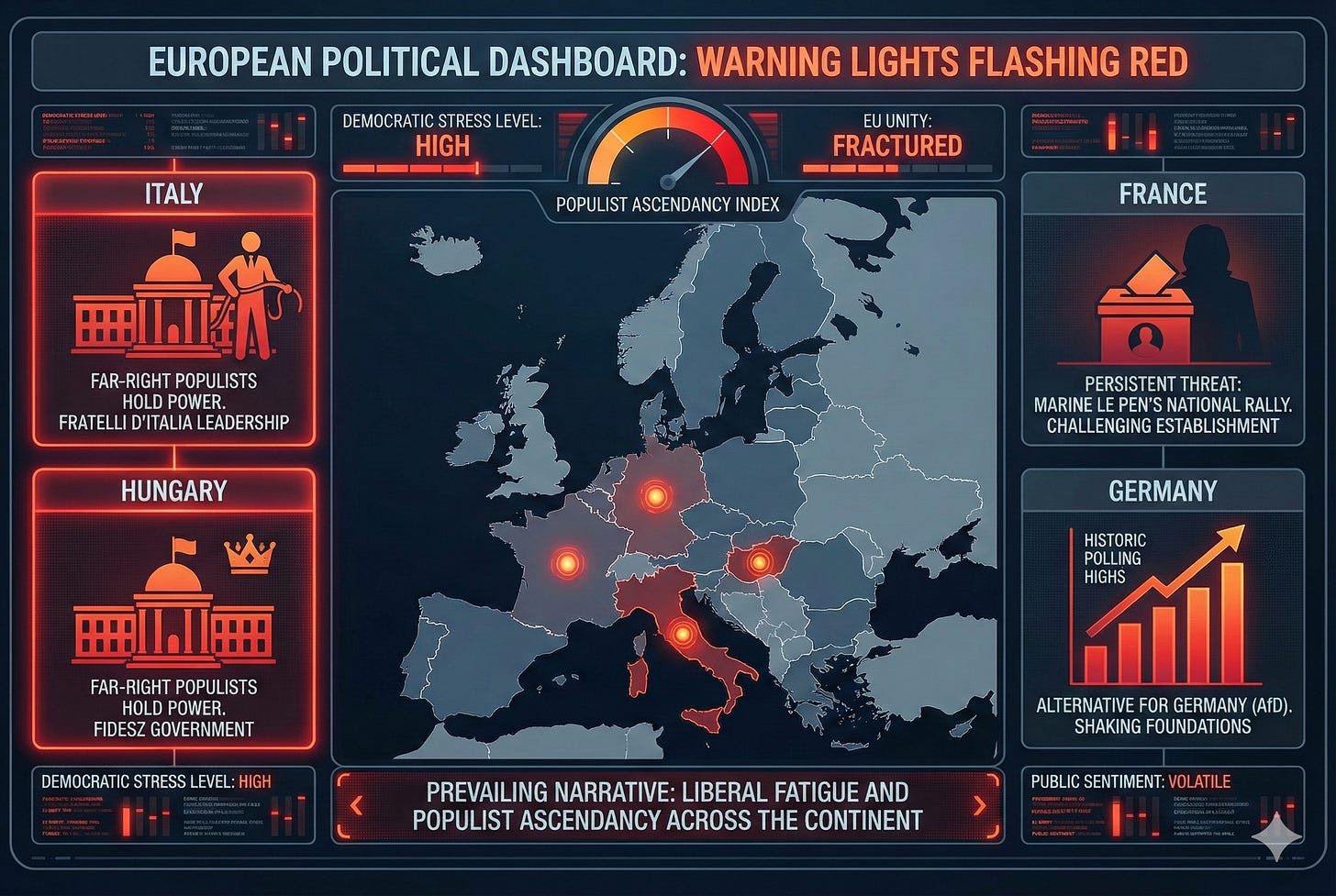

If you look at the political dashboard of Europe right now, the warning lights are flashing vivid red. In Italy and Hungary, far-right populists hold the reins of power. In France, Marine Le Pen’s National Rally is a persistent, formidable threat to the centrist establishment. In Germany, the Alternative for Germany (AfD) is polling at historic highs, shaking the foundations of the republic. The prevailing narrative is one of liberal fatigue and populist ascendancy.

Yet, there is a glitch in this data set. One country on the continent stands out as a glaring, almost confusing exception: Denmark.

While center-left parties across Europe have fragmented or collapsed under pressure from the nationalist right, Denmark’s Social Democrats have not just survived; they have maintained power for more than six years. They haven’t done this by moving to the center on economic issues. They remain fiercely committed to the high-tax, high-service welfare state that Americans often associate with Bernie Sanders.

Their success is built on a ruthlessly strict focus on an issue that has traditionally been the Achilles’ heel of Western liberals: immigration. The Danish model suggests a complicated, perhaps uncomfortable truth about modern governance. To save liberal institutions, Denmark’s leaders decided they had to embrace illiberal border policies.

The 2015 System Crash

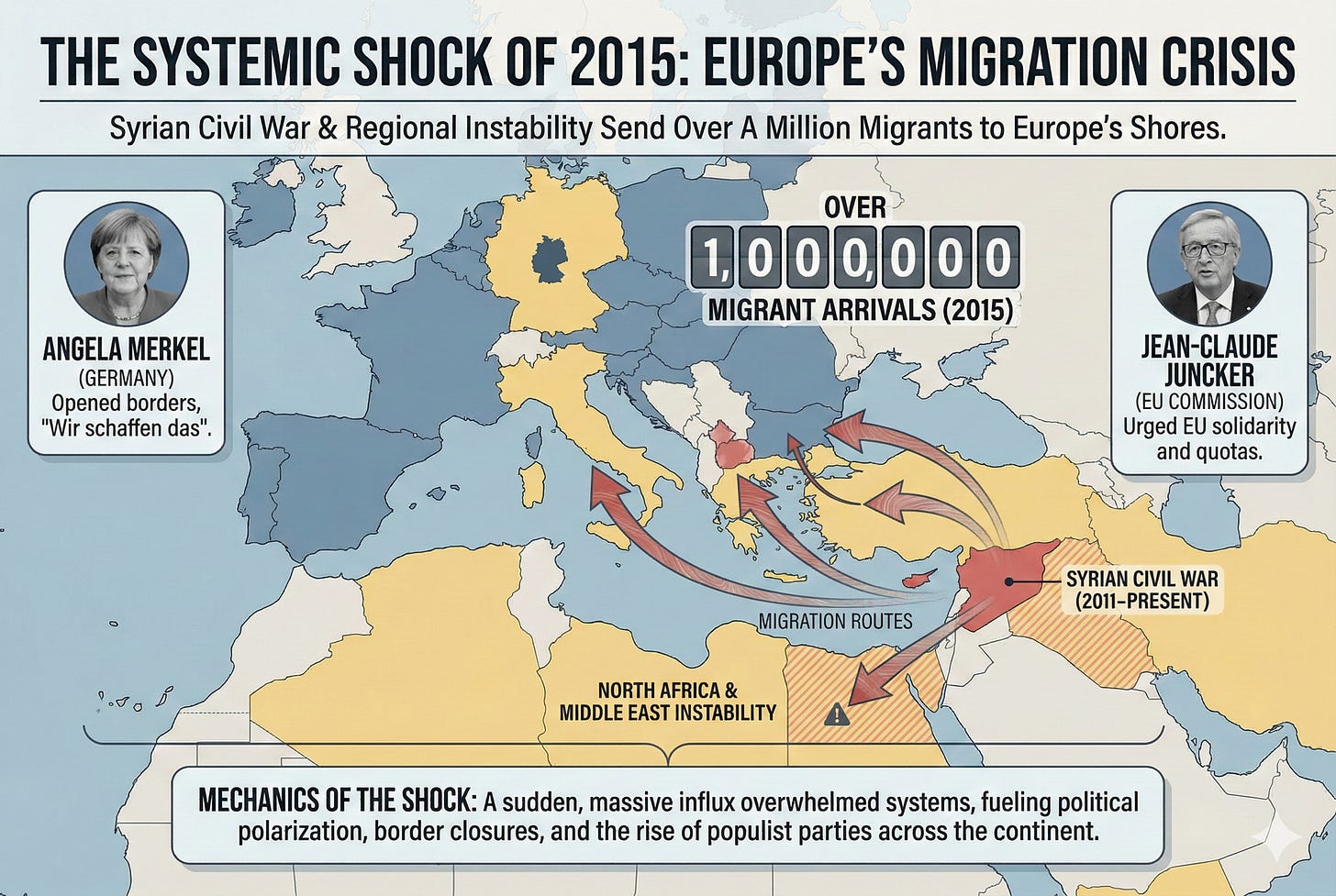

To understand the mechanics of this shift, we have to rewind to the systemic shock of 2015. This was the moment when the Syrian civil war and instability across North Africa and the Middle East sent more than a million migrants toward Europe’s shores.

The post-World War II refugee system, designed for a different era and far smaller numbers, buckled. It was a geopolitical stress test that irrevocably reshaped the continent’s politics, fueling the rise of reactionaries who promised simple solutions to complex demographic shifts.

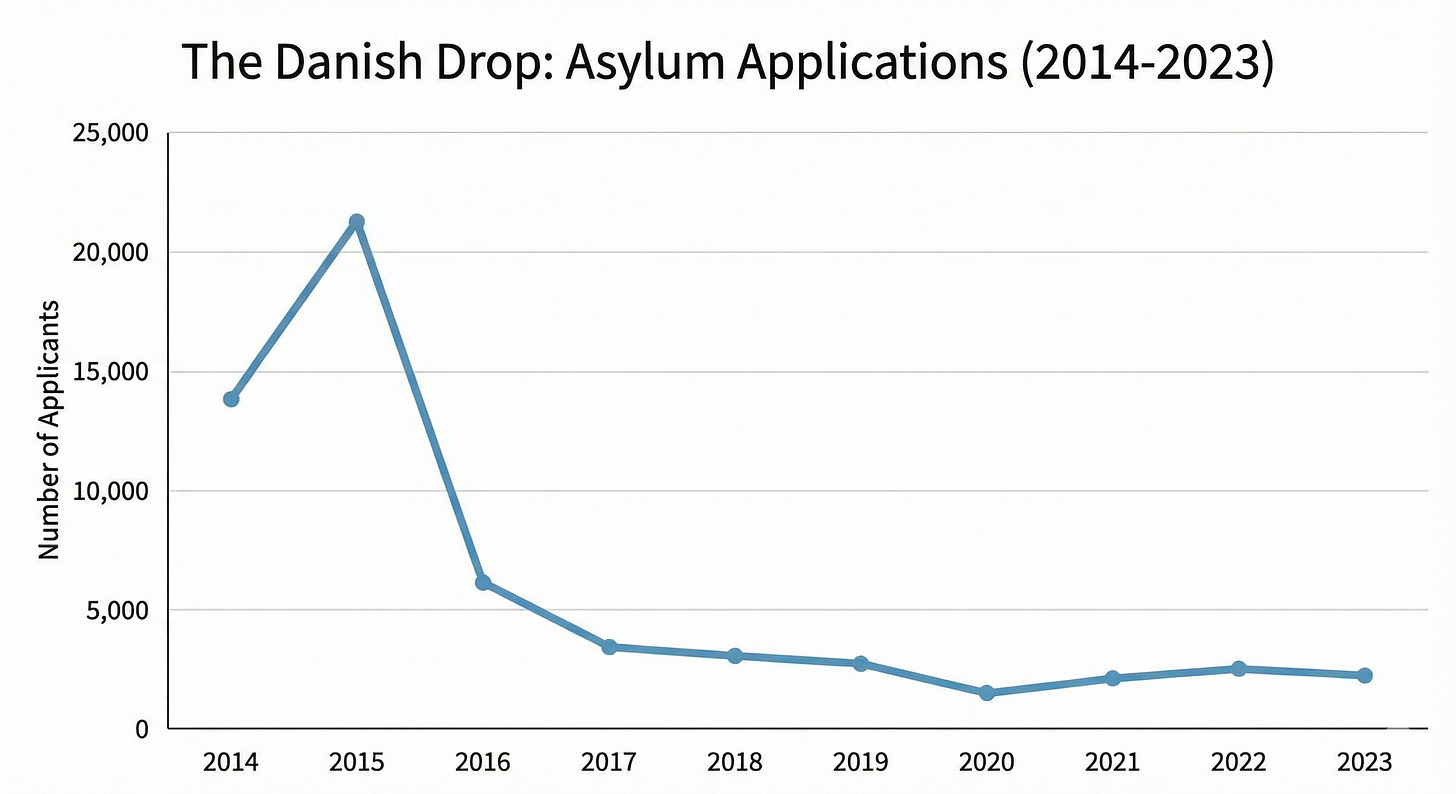

You can see the scale of that disruption in this breakdown of the crisis:

Most European nations responded to the crisis in a chaotic manner, alternating between welcoming newcomers and retreating in fear. Denmark, a culturally homogeneous country with little history of large-scale immigration before the late 20th century, executed a hard pivot. They didn’t just tweak the settings; they overhauled the operating system.

The country made refugee status temporary, signaling that arrival was not a guarantee of permanent residency. In 2016, they passed the controversial “jewelry law,” allowing police to seize assets from asylum seekers exceeding roughly $1,500 in value to offset the cost of their state-funded upkeep. It was a policy widely condemned by international human rights groups, but it sent a clear, unmistakable signal.

The Zero-Sum Calculation

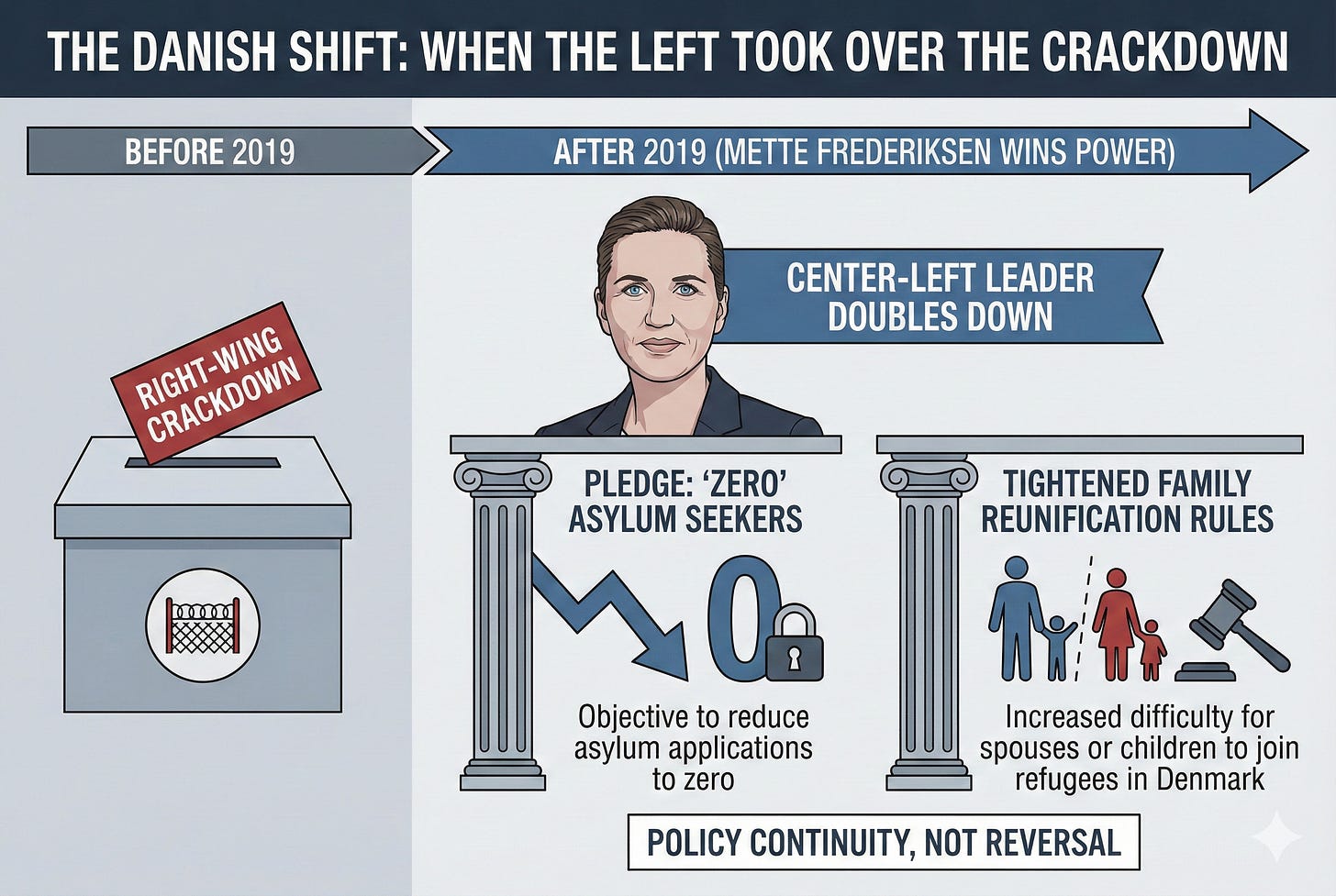

The truly pivotal moment, however, wasn’t when the right cracked down. It was when the left took over the crackdown.

When center-left leader Mette Frederiksen won power in 2019, she didn’t reverse course. She doubled down. She pledged to reduce the number of asylum seekers to “zero.” Her government tightened family reunification rules, making it harder for spouses or children to join refugees already in the country.

They also began a controversial program to rehouse people living in what the government explicitly labeled “parallel societies”—enclaves with high concentrations of non-Western residents and higher rates of unemployment or crime. The message was blunt: integration was not optional, and the state would force it if necessary. Furthermore, Denmark instituted a tiered approach to newcomers, warmly welcoming Ukrainians fleeing the Russian invasion while simultaneously moving to revoke the residency permits of some Syrian refugees, arguing parts of Syria were now safe for return.

The results of this hardline algorithm have been dramatic from a data perspective. Asylum applications didn’t just dip; they cratered to levels not seen since the Cold War.

The Netflix Analogy of the Welfare State

Why would a center-left government in one of the world’s happiest nations, the cradle of “hygge,” impose some of Europe’s strictest measures?

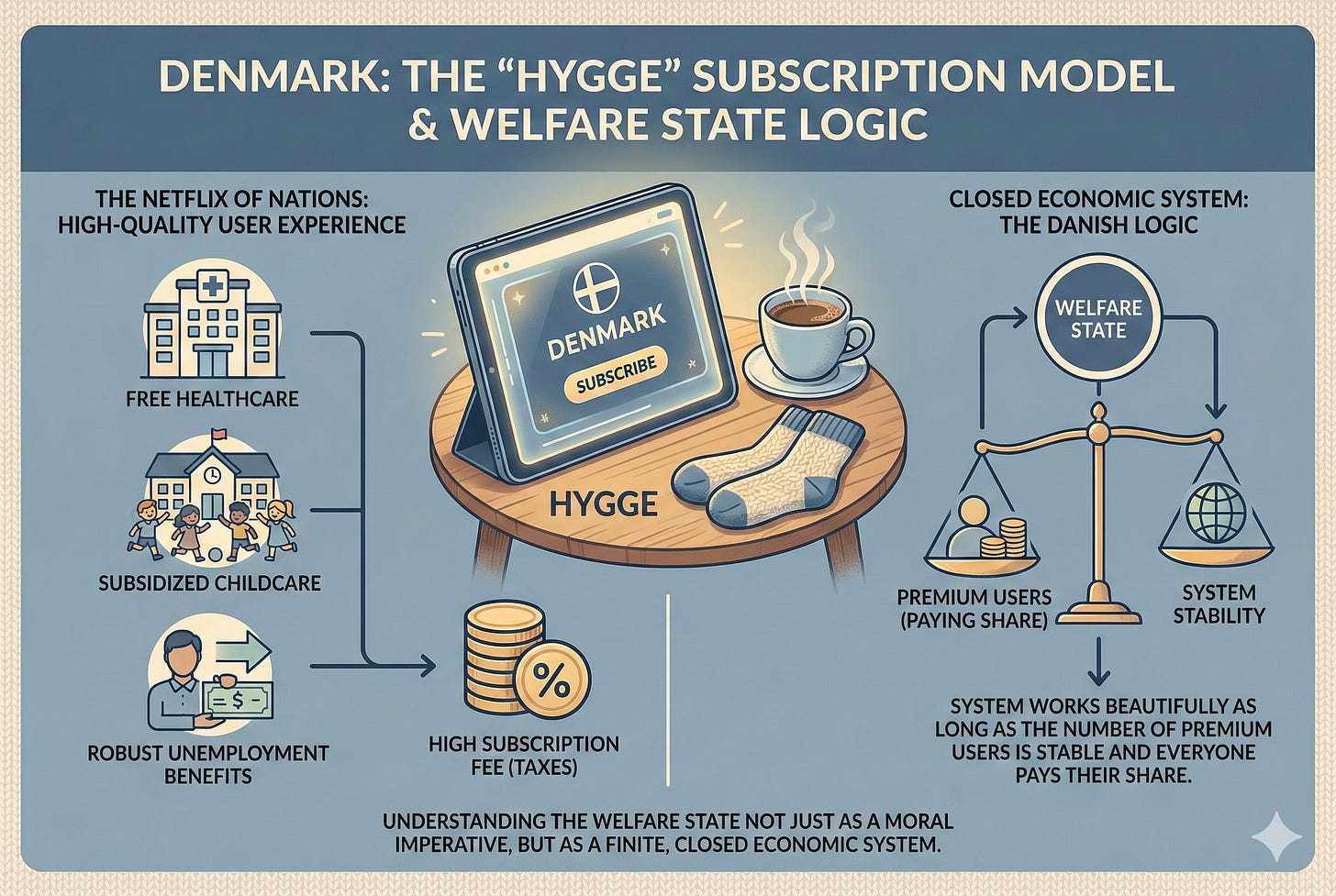

This is where the Danish logic becomes fascinating. It relies on understanding the welfare state not just as a moral imperative, but as a closed economic system, much like a subscription model.

Think of Denmark as the Netflix of nations. It offers an incredibly high-quality user experience—free healthcare, subsidized childcare, and robust unemployment benefits—but the subscription fee (taxes) is very high. The system works beautifully as long as the number of premium users is stable and everyone pays their share.

In interviews, Prime Minister Frederiksen has argued that tough migration laws are actually designed to protect progressive ideals. Her contention is that rapid, low-skilled migration disproportionately hurts Denmark’s existing working class by increasing competition for low-wage jobs and straining access to affordable housing and schools.

If you have too many people accessing the premium content without having paid the subscription fee over time, the service degrades for everyone. Eventually, the subscribers revolt.

Mattias Tesfaye, a key minister behind these policies and himself the son of an Ethiopian refugee, summarized this paradox succinctly to The Economist: “The social democratic welfare state can only survive if we have migration under control.”

For a deeper dive into how this political shift occurred on the ground, this report offers excellent context:

Crucially, in almost every area other than immigration, the Danish Social Democrats have stayed true to their leftist roots. They continue to fund generous public services and maintain strong worker protections. They simply built a very high wall around their garden.

The Solidarity Trade-Off

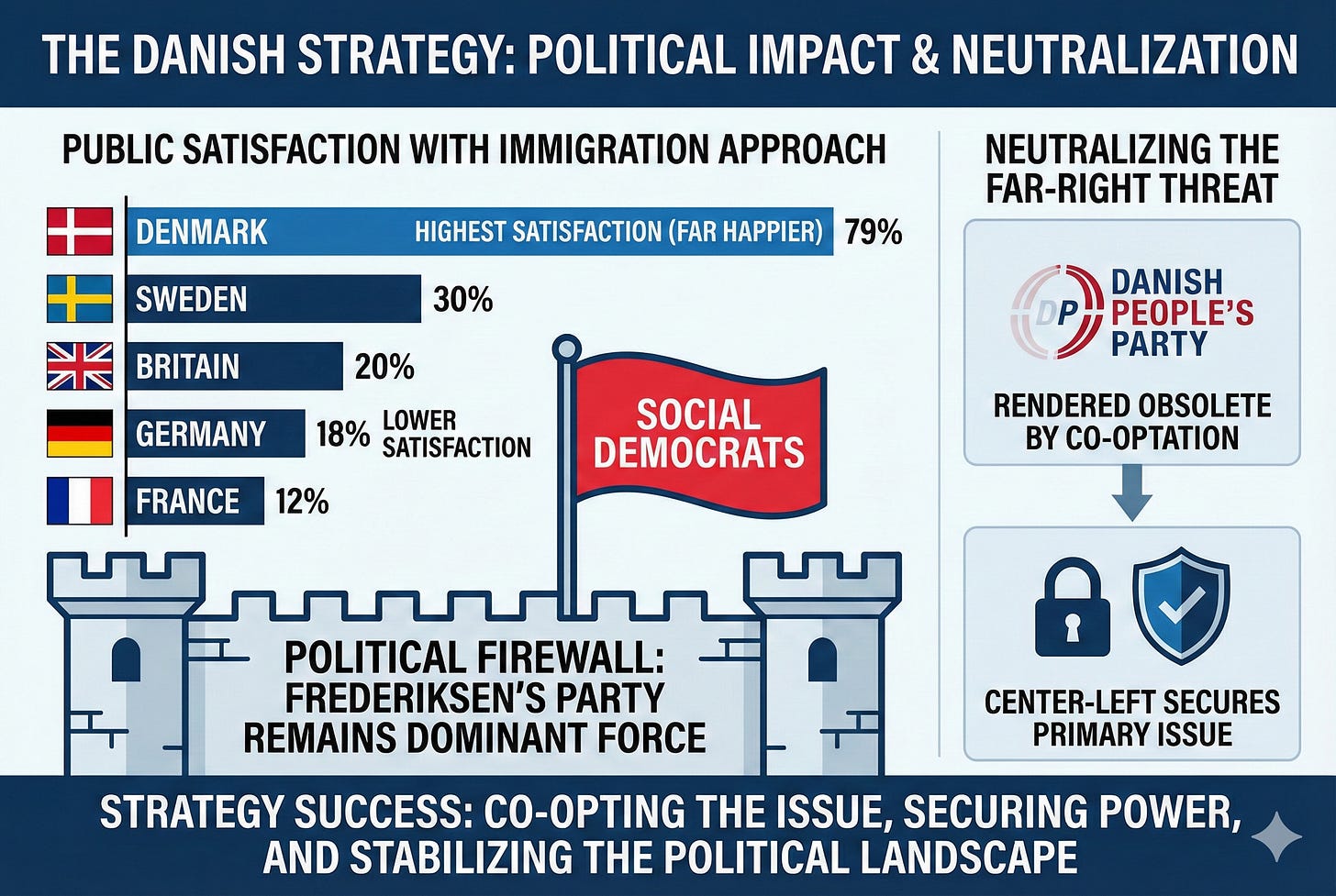

The political impact of this strategy has been undeniable. Polling consistently shows that Danes are far happier with their government’s approach to immigration than their counterparts in Sweden, Britain, Germany, or France.

This satisfaction has translated into a resounding political firewall. Frederiksen’s party remains the country’s dominant political force. Most notably, her stance has largely neutralized the far-right populist threat of the Danish People’s Party. By co-opting their primary issue, the center-left rendered the far-right obsolete.

The broader lesson here for left-of-center parties in the West is uncomfortable but perhaps unavoidable. More than two decades ago, author David Goodhart defined this as the “progressive dilemma” in Prospect magazine. He argued that modern states face a trade-off between “solidarity” (high social cohesion and generous welfare paid out of a progressive tax system) and “diversity” (openness to a wide range of people and values).

You can have a high-trust, high-welfare society, or you can have high levels of rapid immigration. Goodhart argued it is very difficult to have both simultaneously. Denmark’s liberals looked at that trade-off and unapologetically chose solidarity.

The hard truth that the Danish model presents to Western liberals is this: many voters do not see their nation purely as a set of abstract laws and economic institutions. They see it as a bundle of emotions, shared identities, and cultural values. When established parties ignore or dismiss these feelings as illegitimate, voters don’t stop having those feelings. They simply turn to the populists on the right, who are more than willing to handle the issue with greater severity and often outright cruelty.

Now, other European countries are looking to download the Danish software. The UK’s ruling Labour Party, led by Keir Starmer, is already citing Denmark as inspiration for its own tougher asylum laws as it tries to stave off challenges from the right.

Denmark has provided a proof of concept. The question remaining for the rest of the liberal West is whether the price of copying it—trading open borders for the preservation of the welfare state—is one they are willing to pay.