The Three-Trillion-Dollar Gamble

The chips are real; the leverage is invisible

The most important transaction in the history of artificial intelligence did not happen in a laboratory or a server room. It happened in the quiet, climate-controlled offices of a debt capital markets team in Manhattan. There, a former Ethereum miner turned cloud provider named CoreWeave secured a $7.5 billion facility led by Blackstone.

The billions were not secured by vast real estate holdings or decades of recurring revenue. They were secured by Nvidia H100 chips. Tens of thousands of them. Hardware that, at the time of the deal’s structuring, had barely left the fabs in Taiwan.

For decades, the technology industry operated on a simple premise. You sell equity to venture capitalists to fund growth. You give away a piece of the company to buy time. But when you need to buy specialized silicon at $30,000 per unit to compete in an arms race, equity is too expensive. It is too slow. You need debt. Massive, industrial-scale debt.

That $7.5 billion deal was a signal flare. It announced that the AI revolution had graduated from a software challenge to a capital-expenditure war. We are witnessing a projected $3 trillion infrastructure buildout, a sum that rivals the GDP of the United Kingdom. But unlike previous infrastructure booms, this one is being financed with a speed and opacity that makes traditional bankers sweat.

The money is moving into Neo-clouds, agile, risk-tolerant startups, and through off-balance-sheet vehicles that keep the true leverage hidden from the public eye. It forces us to ask a question that the market is currently trying very hard to ignore. What happens when the fastest-depreciating asset in history becomes the collateral for the largest infrastructure buildout in history?

This is not a bet on AI. It is a bet on refinancing.

The Race Against the Clock

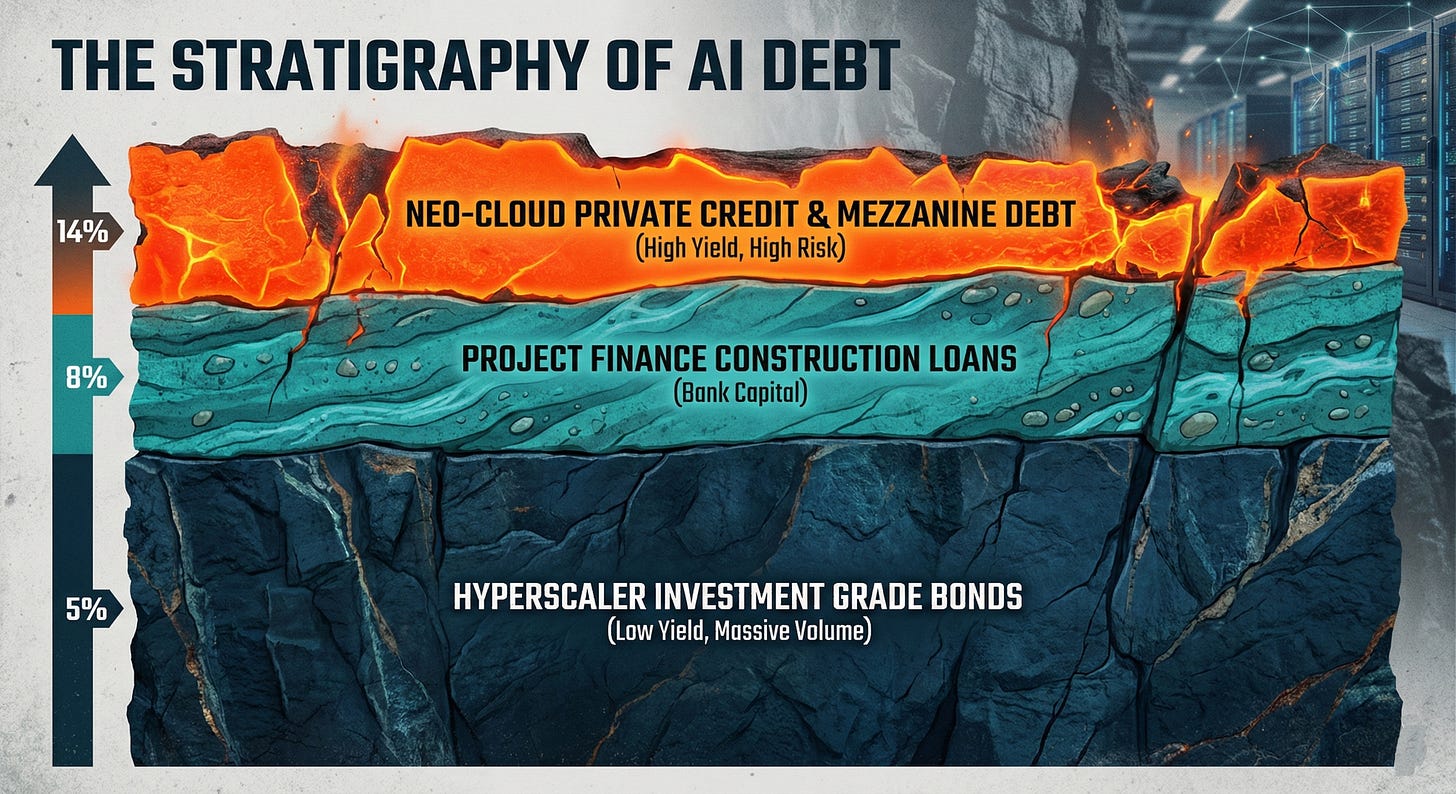

The figure is difficult to conceptualize. Morgan Stanley estimates that by 2028, the global investment in chips, servers, and data centers will hit $3 trillion. To fund this, the tech sector has broken its long-standing allergy to leverage. They are tapping every corner of the credit market, from investment-grade corporate bonds to the darker, more expensive corners of private credit.

This is not standard corporate borrowing. In the past, a company like Google or Microsoft would simply issue bonds based on its pristine credit rating. Today, the demand is so voracious that the market has bifurcated. You have the Hyperscalers, the Microsofts and Amazons, borrowing at rates just above sovereign debt. Then you have the Neo-clouds. These entities are effectively special purpose vehicles for turning electricity and silicon into tokens. They are paying double-digit yields to access capital, effectively mortgaging their hardware to fund the very buildings that house it.

The problem is not whether the bet is right. It is whether it stays right long enough. Corporate bonds often have maturities of five, seven, or ten years. An H100 has a prime productive life of three or four years before the next generation renders it inefficient. The debt has a longer shelf life than the asset it purchased. In the world of private credit, that mismatch is where the risk lives.

The Illusion of Liquidity

To understand how a startup can borrow billions without crushing its balance sheet, you have to look at the Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV). This is the financial instrument that turns “tech risk” into “infrastructure risk.” In this model, a tech company does not build a data center. It creates a separate legal entity, the SPV, which owns the land and the servers. The SPV borrows the money, builds the facility, and leases it back to the parent company.

This structure allows conservative insurance companies and pension funds to lend money to volatile tech startups. They are not betting on the startup’s software succeeding. They are betting that the physical data center will have value regardless of who occupies it. It is a form of credit ring-fencing that isolates the project from the parent company’s operational chaos.

There is a catch. If the AI model fails, the lenders still own the building and the chips. But ownership is not the same thing as liquidity. A specialized data center filled with last generation’s GPUs is not a generic office building that can be easily repurposed. It is a specific industrial asset. If the tenant defaults, the lender is left holding a very expensive, very hot, aging box of computers.

How Circular Deals Are Driving the AI Boom - This video explains the “circular” nature of funding where cloud providers invest in startups that then buy their cloud services, inflating revenue figures.

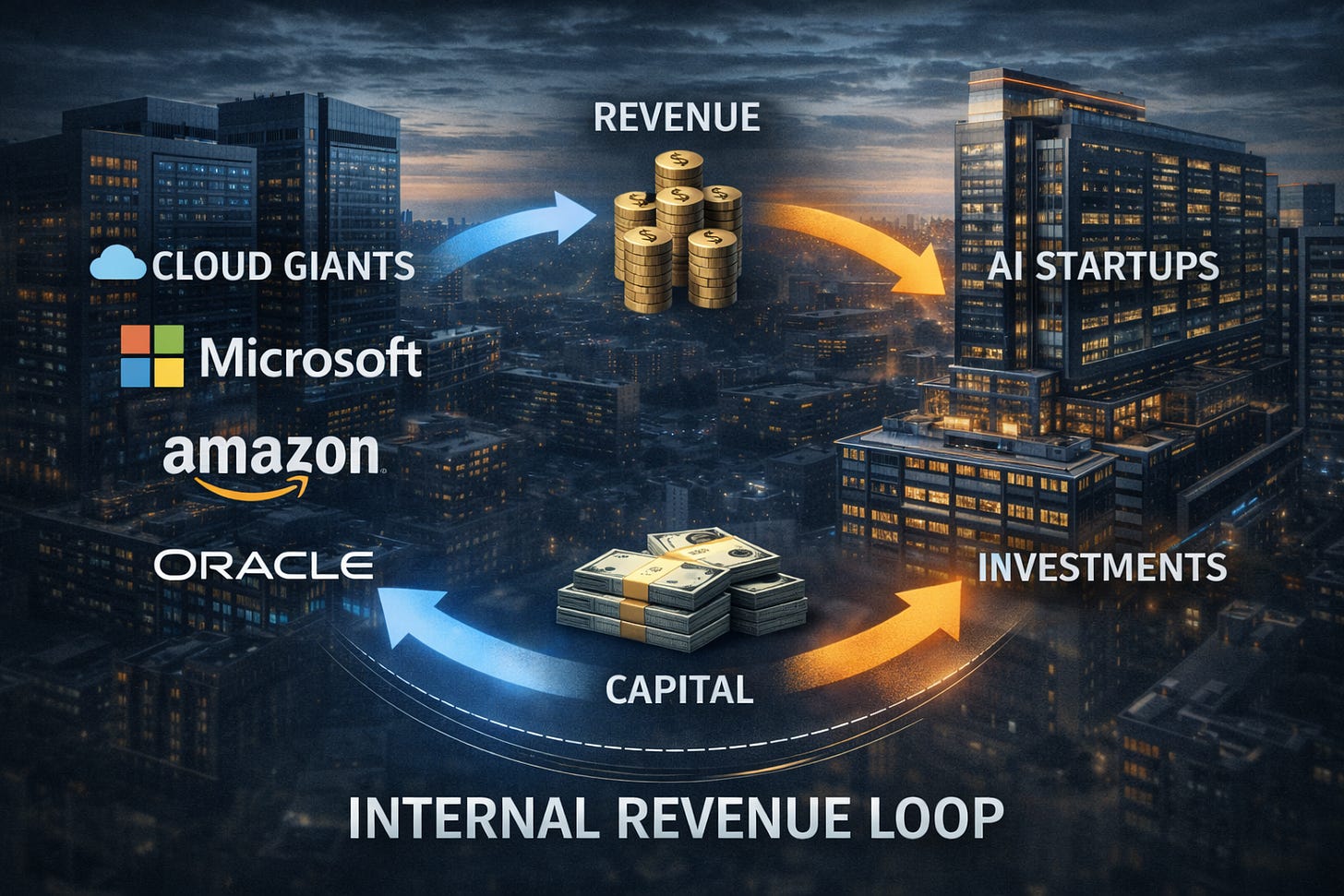

The Echo Chamber of Capital

The complexity of these deals often masks a strange circularity in the market. We see massive revenue growth figures for cloud providers and assume it represents external market demand. Often, it represents an internal loop.

Cloud giants invest billions into AI startups. Those startups, flush with cash, immediately sign long-term contracts to rent cloud servers from the very giants that invested in them. The capital leaves the balance sheet as an investment and returns as revenue. In this ecosystem, growth does not always arrive from the outside. It circulates.

This dynamic creates a moral hazard. It incentivizes the funding of projects not because they are viable, but because they validate the infrastructure spend. It maintains the velocity of money required to service the debt, creating an echo that sounds a lot like market validation.

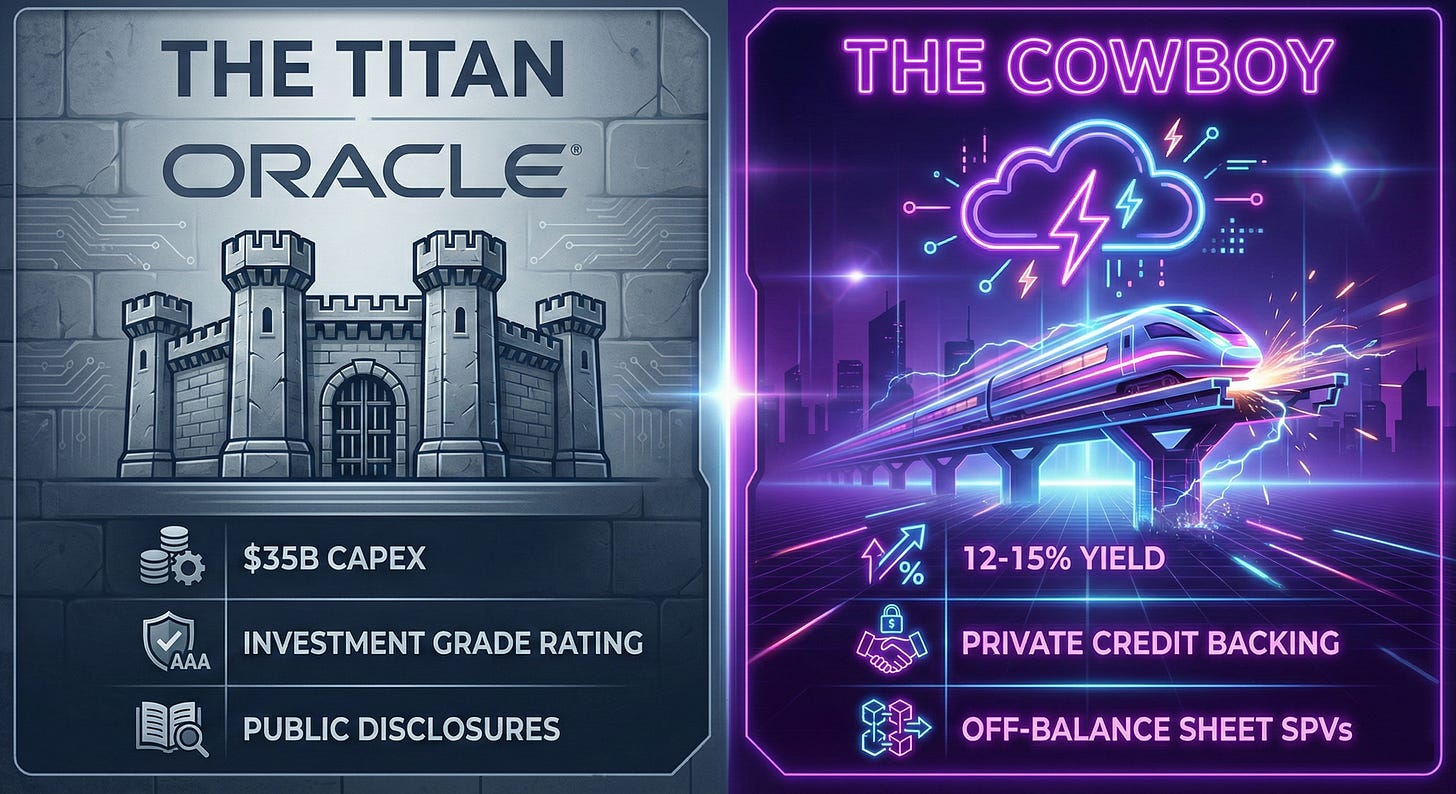

Titans and Cowboys

The market is currently split into two distinct realities. On one side, you have Oracle, a titan of the industry. Oracle is aggressively pivoting to AI, with capital expenditures hitting $35 billion for fiscal year 2025. To fund this, reports suggest they are considering cutting up to 30,000 jobs. It is a brutal reallocation of resources from human capital to silicon capital. But Oracle’s debt is visible, rated, and understood. They are trading flexibility for survivability.

On the other side are the cowboys. The Neo-clouds are all-in bets on the future of compute. Their cost of capital is significantly higher, often in the mid-teens, reflecting the existential risk they face. They are trading survivability for speed. If the demand for AI compute softens even slightly, these companies are left with billions in depreciating hardware and interest payments they cannot meet.

Financing the Obsolescence

The most exotic part of this market is “GP Finance”, financing the Graphics Processing Units themselves. Lenders are now writing loans against clusters of chips. This is unprecedented. Historically, infrastructure finance is backed by things that last longer than the loan. Bridges. Toll roads. Power plants. Even airplanes have a lifespan of decades.

We are now financing infrastructure that rots. Not physically, but economically. The rate of technological obsolescence in AI is blistering. If Nvidia releases a new architecture that makes the H100 obsolete faster than projected, the collateral for billions of dollars in loans evaporates. The lenders are betting not just on the borrower’s solvency, but on the pace of innovation slowing down just enough to let them get paid back. It is a financing model that is structurally at war with the technology it enables.

The Invisible Ledger

The ultimate risk in this $3 trillion buildout is not the debt itself. It is the lack of information. Public companies like Oracle must disclose their lease commitments, giving analysts a breadcrumb trail to follow. But in the private markets, where the most aggressive deals are happening, there is no such requirement.

This creates a systemic blind spot. We do not know the absolute scale of the leverage. We do not know how many loans are cross-collateralized against the same assets. The last time markets discovered massive leverage only after it mattered, it was not because the debt was illegal. It was because it was invisible.

| Tech Firms Unleash AI Spending Spree | 150,000+ views | Placement rationale: This Bloomberg segment details the sheer scale of the spending from the “Big Tech” perspective, contrasting with the private credit angle.]

The Hum

The AI infrastructure boom is a marvel of engineering, not just in terms of teraflops and parameters, but in terms of yields and covenants. The financial industry has constructed a mechanism to pour concrete and secure silicon at a pace that defies historical precedent.

But if you stand outside one of these massive new data centers, you hear the hum of thousands of fans spinning in unison. Inside, the lights blink on the server racks, processing queries, training models, consuming electricity. In a spreadsheet in New York, the interest on the loan that bought them compounds daily. The chips degrade daily. The race is to see which line on the graph crosses zero first. The building is quiet. The clock is ticking.

Da*n...

The next step is when they package this debt in mezzanine bonds. Moodys will rate the bonds A- and sell it to the public.

Outstanding piece. The parallel between financing infrastructure that rots economically versus traditional infrastructure that holds value is particulary sharp. In my experiance watching tech cycles, the most dangerous moment isn't when everyone knows the risk, it's when the financing structure makes it invisible to the people taking it on.